Jan 29, 2026

Vuk Velebit, Aleksa Jovanović, Petar Ivić

IMEC As The Crucial Future Corridor And Why Serbia Must Not Miss It

Why IMEC will reshape Eurasian trade and why Serbia must position itself now to secure strategic relevance.

”We strongly believe in the future of this infrastructural, commercial, and political project that will connect India to Trieste. - Antonio Tajani, Foreign Minister of Italy

Introduction

Connectivity is no longer a matter of infrastructure, it is a matter of placement. In a world where supply chains are being re-engineered under geopolitical pressure, the decisive question for mid-sized states is not whether they can build roads and railways, but whether they can insert themselves into the next strategic corridor before the map hardens without them. The announcement of the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) at the 2023 G20 Summit captured this shift, signaling “new momentum in global connectivity geopolitics.” IMEC is more than a transport project, it is a strategic effort to realign trade, investment, and supply chains between South Asia, the Gulf, and Europe.

The importance of the corridor, aside from economy, is in the sphere of politics and power. Given the word play of Italy’s Foreign minister Antonio Tajani calling IMEC the “Cotton Route”, the project aims to rival the ancient “Silk Road” in importance, and of course, its modern day counterpart, the Chinese “Belt and Road Initiative”. Just like with the “Silk Road”, whoever stands at the end routes wins. Thus, the India and the EU have a common rival, having to topple China in this supply chain contest. Nevertheless, European countries (including Serbia) would benefit from this competition, especially if they link themselves to the great artery of IMEC.

In this emerging corridor-based order, Serbia and India are unusually well-positioned to translate political compatibility into economic leverage. Both countries have long prioritized strategic autonomy, a modern continuation of their Non-Aligned legacy, while their economies are more complementary than competitive. The opportunity is therefore not symbolic diplomacy, but practical corridor statecraft: using IMEC’s westward logic to deepen Serbia–India cooperation in manufacturing, digital services, logistics, and security. This analysis examines how a Serbia–India partnership can scale in the IMEC era, linking India’s westward expansion with Serbia’s European gateway role, and concludes with actionable priorities to convert alignment into lasting advantage.

The IMEC Era as a Redefinition of Eurasian Connectivity

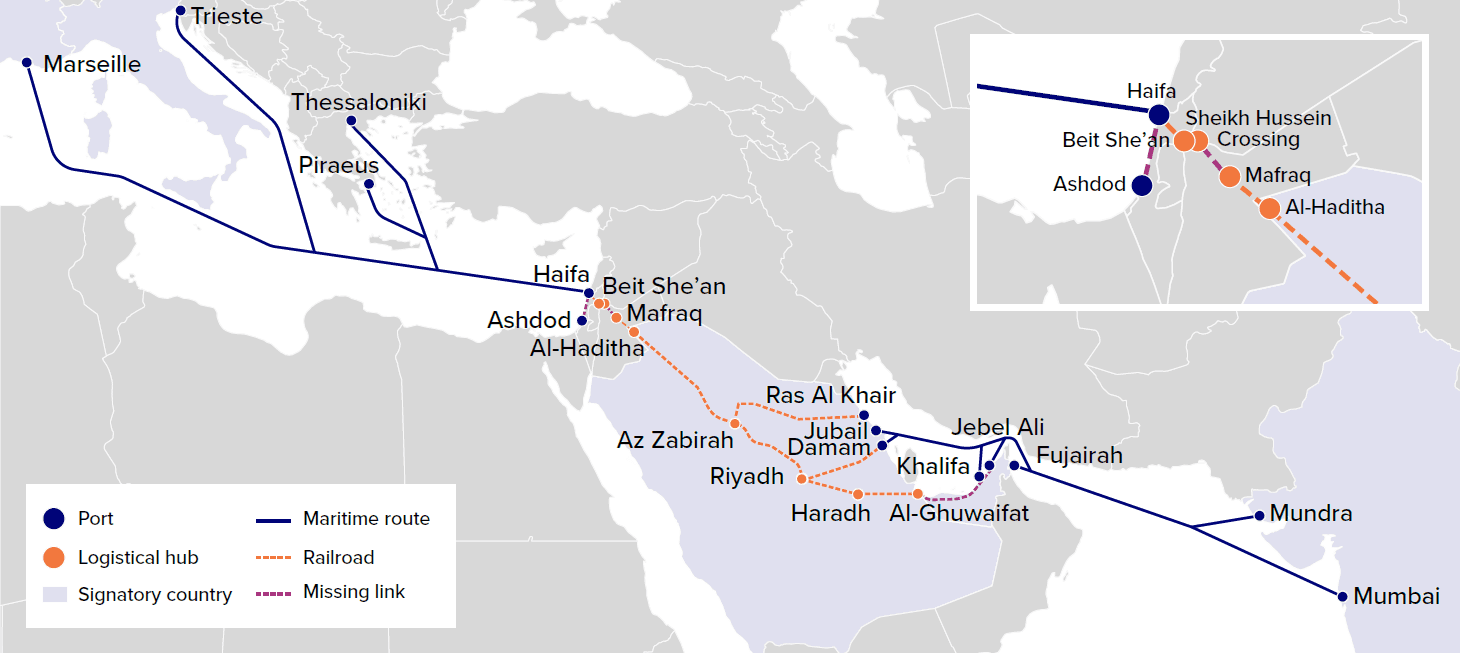

IMEC Corridor Route - Source: Atlantic Council

What IMEC is and how it is designed?

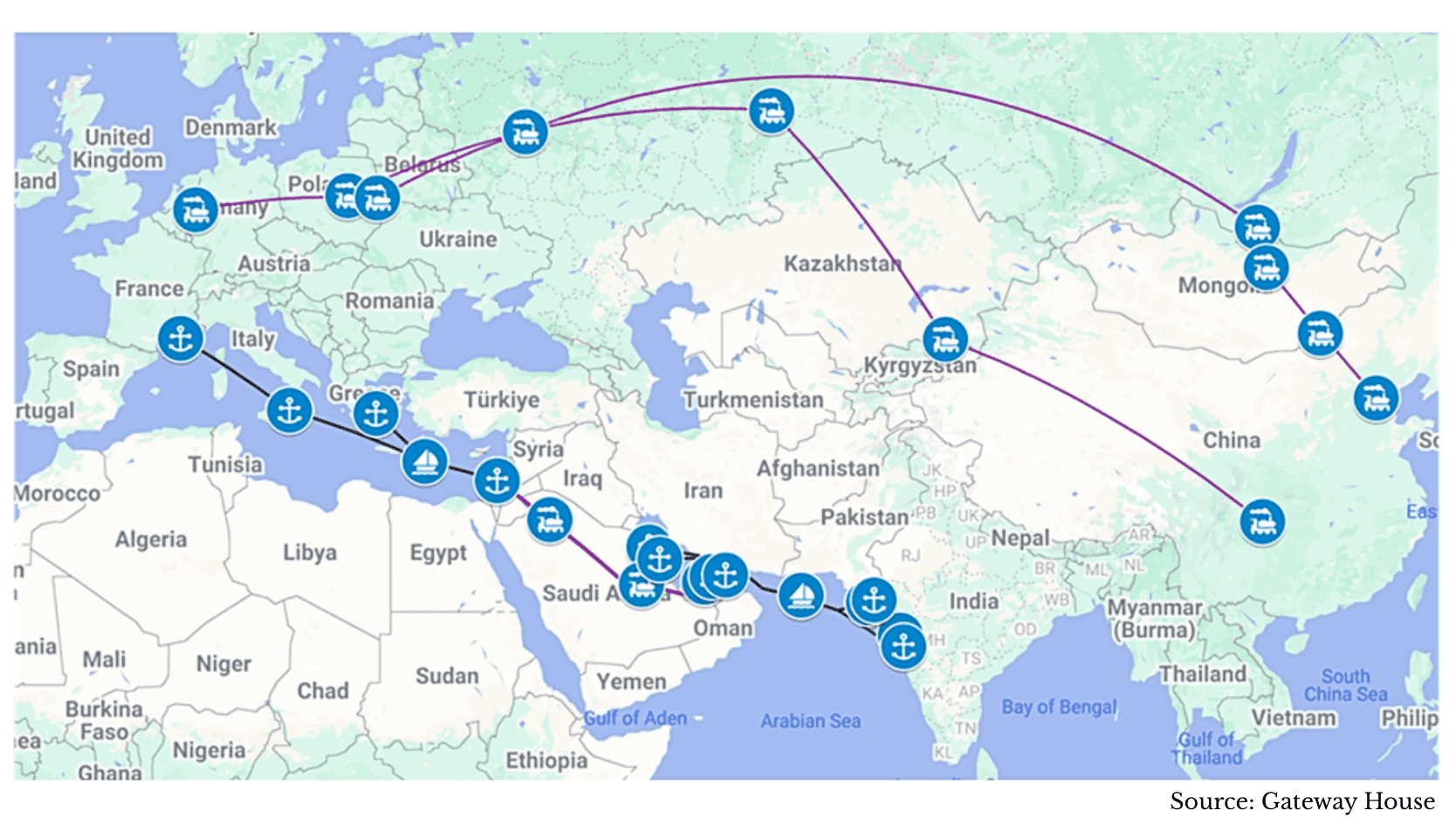

The India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is a planned multi-modal connectivity corridor intended to link India with Europe through the Gulf and the Eastern Mediterranean, combining maritime routes with expanded rail infrastructure. The corridor was announced and politically endorsed at the 2023 G20 Summit, and later formalized through a Memorandum of Understanding among participating partners. Conceptually, IMEC is designed as an integrated route that moves cargo from India’s west coast to the UAE by sea, then across the Arabian Peninsula via rail through Saudi Arabia and Jordan, onward through Israel, and finally into Europe through Mediterranean gateways (commonly framed through entry points such as Greece or Italy). Analysts often describe IMEC as consisting of two linked segments: an eastern corridor (India to the Gulf by sea) and a northern corridor (Gulf to Europe via rail plus onward maritime connectivity).

Why IMEC exists? Politics, Strategy, and Coalition Logic

IMEC is best understood as a geopolitical and geoeconomic project, not simply a transport initiative. Its launch reflects a convergence of strategic interests among India, key Gulf states, the European Union, and the United States, all seeking to shape the next architecture of Eurasian connectivity. In the strategic debate, IMEC is widely viewed as a counterweight to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, offering an alternative framework that is anchored in a U.S.–EU-supported coalition and aligned with India’s rise as an independent power center. For Washington and Brussels, the corridor is also a mechanism to pull India deeper into westward connectivity and standards-setting, while giving Europe an additional strategic option in infrastructure geopolitics. The importance of the corridor only intensifies after the signed an FTA between the EU and India on January 27, which aimes to slash tarrifs and boost trade. For Gulf partners, IMEC fits national diversification agendas, positioning Saudi Arabia and the UAE as high-value logistics hubs capable of capturing trade flows, investment, and industrial spillovers linked to corridor infrastructure. IMEC also decreases risk of Houthi disruption of global trade, which happened to be a major problem in recent years.

While China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a China-led global infrastructure network spanning dozens of countries, the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor is positioned as a multilateral, US- and European-backed alternative that focuses on transparent, sustainable connectivity between India, the Middle East, and Europe rather than China’s debt-financed model.

What IMEC changes? Trade routes, Resilience, and Europe’s Gateway Competition

If implemented at scale, IMEC could reshape Eurasian commerce by creating faster, more resilient sea–rail hybrid routes connecting India and Europe. One of its core rationales is supply-chain security. Corridor planners and supporters frame IMEC as a way to strengthen India–Europe supply routes and reduce dependence on congested or vulnerable chokepoints such as the Suez Canal, a concern sharpened by recent shocks and disruptions in global logistics. Beyond route diversification, IMEC is expected to stimulate major infrastructure investment along its path, especially in the Middle East, where ports, rail corridors, and logistics zones are being positioned to benefit from corridor traffic. Within Europe, IMEC also intensifies competition over which ports become the main gateways: hubs such as Trieste, Piraeus, and Marseilles have been cited as leading candidates, and Trieste in particular has promoted its rail connections into Central and Eastern Europe as a key advantage. The broader strategic takeaway is clear: in a corridor-driven era, connectivity increasingly determines industrial placement and influence. States and regions that secure node status gain investment momentum, while those outside risk being bypassed.

Why Serbia and India Are Natural Partners & Legacy of Sovereignty

Serbia and India share a diplomatic heritage anchored in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). In 1961, Belgrade hosted the first NAM Summit, co-founded by Yugoslavia’s President Tito and India’s Prime Minister Nehru, affirming a bloc of countries committed to independence from Cold War power blocs. This legacy continues to shape both nations’ worldviews. Serbia, as the principal successor of non-aligned Yugoslavia, and India, as the largest NAM country, have political DNA favoring neutrality and strategic autonomy. Both nations thus reflexively resist external pressures that conflict with their national interest. A contemporary example is their stance on international sanctions: India and Serbia have condemned breaches of sovereignty (India supports Serbia on Kosovo and Serbia supports Ukraine’s territorial integrity) yet both have refused to join Western sanctions on Russia.

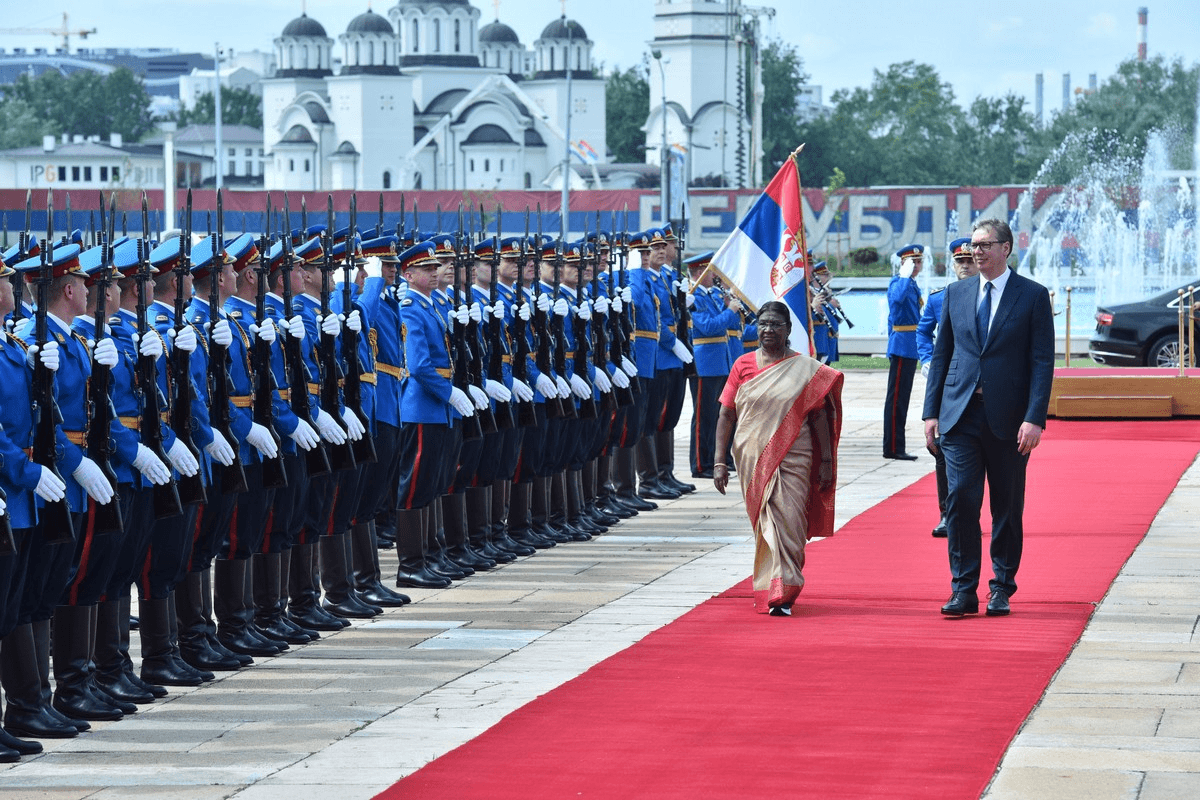

The historic state visit by Indian President Droupadi Murmu to Serbia, the first-ever head-of-state visit between the two countries, symbolized a deepening of longstanding diplomatic friendship and opened the door to expanded cooperation across politics, trade, defence, technology, agriculture and culture.

This creates a comfort level and trust, Belgrade knows New Delhi will respect its independent decisions, and vice versa. Crucially, both see strategic self-reliance as empowering partnership rather than hindering it. Free from hegemonic alliances, they can cooperate on equal footing. This political compatibility translates into an easier alignment of agendas in forums like the United Nations, where Serbia and India often support each other’s candidacies and resolutions. The legacy of sovereignty through NAM thus forms a strong ideological foundation for a Serbia–India partnership in the IMEC era, it is a partnership not of convenience, but of conviction that an interconnected multipolar world benefits from autonomous yet like-minded actors joining hands.

Serbia’s Position: A European Gateway for India’s IMEC Ambitions

“Trieste has always been the port of Central European countries and the Balkans, and the Balkans have already stated that they want to connect with the railway to Trieste. We need to start working now to make people understand the importance of the Cotton Route, an extraordinary opportunity for our companies and for a country like ours, with great capabilities in sectors such as submarine cables and railways." - Antonio Tajani, Foreign Minister of Italy

Serbia’s EU accession trajectory can function as a competitive economic asset, not a limitation, for businesses seeking speed and optionality. Serbia is structurally aligned with European market requirements, yet retains enough policy space to deploy targeted incentives, faster permitting, and investor-tailored support in ways that are often harder to replicate inside the EU’s more rigid industrial-policy environment. This “EU-adjacent” positioning becomes even more valuable as India’s access to Europe enters a new, and still uncertain, trade phase. As Reuters reported in January 2026, India and the EU concluded a long-negotiated free trade agreement, but the deal will still require European Parliament ratification that could take at least a year, with political hurdles that may delay implementation; key elements such as investment protection are also being negotiated separately, narrowing the initial FTA scope to goods, services, and trade rules. In that interim period, while exporters still face regulatory friction and unresolved issues around services mobility, standards compliance, and carbon-related measures, Serbia becomes a practical platform for Indian companies to establish early industrial presence, reduce execution risk, and build EU-facing supply chains before the rules fully settle. In other words, Serbia is not “outside the EU” in a passive sense, it actually offers European proximity without maximum rigidity, allowing firms to lower costs without sacrificing market access.

Serbia has deliberately operationalized this positioning as an industrial base at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. Through Free Economic Zones, plug-and-play facilities, and logistics parks connected to rail and highway networks, especially around Belgrade and Niš, Serbia offers investors a scalable manufacturing environment with improving infrastructure and competitive production costs. These advantages are already visible in Indian investment patterns. Motherson has built a major footprint in Serbia, operating multiple facilities and supplying leading European carmakers, while Sona Comstar expanded into Serbia through acquiring a majority stake in the high-tech firm Novelic, integrating Serbian engineering talent into global automotive electronics. In parallel, TAFE acquired the IMT tractor brand and pursued production revival in Belgrade, using Serbia’s location to target EU and regional markets. Taken together, these cases underline Serbia’s core proposition. It is geographically European, commercially competitive, and structurally open, enabling Indian firms to establish a credible foothold that is export-ready from day one.

Sectoral Leverage Points

Sector | Strategic rationale combined with IMEC relevance |

|---|---|

Pharmaceuticals & Healthcare | Pharmaceuticals are a natural anchor for Serbia–India cooperation because both sides bring structurally complementary advantages. India is the world’s 3rd-largest pharmaceutical producer by volume and accounts for roughly 10% of global production by volume, sustaining its “pharmacy of the world” profile. Serbia, meanwhile, has a credible pharma industrial base and a regulatory pathway that can align with EU market requirements, opening space for joint manufacturing of generics, EU-facing production lines, and corridor-resilient supply chains that combine Indian scale with Serbian proximity. IMEC compresses time-to-market for India–Europe medical supply chains, making Serbia a practical EU-adjacent production and distribution node. |

IT & Digital Services | Digital cooperation matters because it is both economic and strategic, linking service delivery, standards, and security. India’s IT/BPM ecosystem employed 4.5 million people (March 2021) and remains a global engine for software and business services at scale. Serbia complements this with EU-market proximity, competitive costs, and a growing innovation ecosystem, enabling Indian firms to build regional delivery capacity in Belgrade or Novi Sad while Serbian teams gain structured access to Indian markets and platforms. Serbia’s hosting of the GPAI Summit in Belgrade (3–4 December 2024) reinforces alignment and credibility in AI governance conversations. |

Manufacturing & Automotive | Manufacturing is where corridor logic becomes measurable: investment flows to locations that minimize friction, stabilize supply, and serve end markets fast. Serbia offers Indian producers an EU-adjacent industrial base that can support auto-components, electronics, and EV-linked supply chains, leveraging Serbia’s Free Zone infrastructure, engineer-heavy labor pool, and production-cost advantages. This model also works in reverse, where Serbian precision manufacturing and machinery exporters can partner with Indian players to reach South Asian demand as connectivity expands. |

Agriculture & Food Processing | Agriculture cooperation is high-impact because it scales with logistics upgrades, cold-chain capacity, and new market access. Serbia can expand exports into India’s growing consumer market while benefiting from India’s strengths in agri-tech and processing. Demand indicators already exist: India’s FY2023/24 imports from Serbia rose sharply in tobacco ($1.12m → $7.15m) and increased for edible fruits and nuts ($3.34m → $4.12m), signaling where bilateral trade can deepen with targeted facilitation. The opportunity lies in food-processing joint ventures, corridor-enabled logistics, and certification pathways that lift both export value and resilience. IMEC rewards food supply chains that are faster and more reliable, making cold-chain and processing partnerships commercially decisive. |

Defense & Security | Defense and security cooperation, through a Defense Cooperation Agreement signed in 2019, gives the partnership strategic depth because it reinforces autonomy and resilience rather than dependency. Serbia and India share comfort with flexible alignment, enabling selective cooperation in defense industrial production, maintenance, training exchanges, and cyber defense. As connectivity corridors expand, so do vulnerabilities: critical infrastructure, logistics systems, and digital networks require stronger protection and interoperability frameworks. This makes structured Serbia–India cooperation in cyber training, secure communications, and niche defense-industrial linkages not just possible, but strategically rational. |

Institutional Steps to Realize the Potential

To fully unlock the corridor-era partnership, Serbia and India should take concrete institutional measures. These steps will build the enabling environment for businesses and people to collaborate at scale:

Easing Visa and Mobility: Restoring and improving travel access is critical. Serbia unilaterally offered visa-free entry to Indians from 2017 to 2023, spurring tourism and business visits, but later reintroduced visas in line with EU policies. Going forward, the two countries should negotiate liberalized visa regimes. For example, a multiple-entry business visa arrangement or reinstating visa-on-arrival for short stays. Facilitating mobility of professionals, students, and tourists will deepen ties. Establishing direct flights is equally important: currently, travel relies on hubs like Dubai or Istanbul. A direct Belgrade–New Delhi or Belgrade–Mumbai flight would be a game changer for connectivity. Both governments could offer incentives to airlines or code-share partnerships to initiate routes. Simplifying work permits and recognizing each other’s professional qualifications will also encourage the exchange of skilled personnel (IT engineers, researchers, etc.) that is vital for the priority sectors identified.

Banking and Trade Facilitation: A robust financial infrastructure underpins any strategic economic partnership. Serbia and India should work on linking their banking systems more closely. This includes encouraging Indian banks to open representative offices or branches in Belgrade and vice versa, and establishing correspondent banking relationships that reduce transaction costs. Using local currencies in trade settlements could be explored to mitigate currency risk. For instance, a framework for rupee-dinar trade settlements for certain goods. Both countries should also conclude a refreshed Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) to give investors confidence through legal protections (the old India–Serbia BIT is outdated). Additionally, customs procedures need alignment: a Customs Cooperation Agreement can simplify documentation for goods moving along IMEC into Serbia and then to India, perhaps even allowing pre-cleared “green channels” for certified exporters . Aligning standards is another facilitation step – mutual recognition of pharmaceutical Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), or co-operation between India’s BIS and the Serbian Standards Institute, so that products tested/certified in one country are smoothly accepted in the other. Such measures reduce non-tariff barriers and will grease the wheels of commerce.

Infrastructure and Digital Alignment: Serbia and India should ensure they are digitally and physically plugged into the corridor economy. On infrastructure, Serbia’s logistics planners can coordinate with India and IMEC partners so that last-mile linkages are in place: for example, if Trieste (Italy) becomes the IMEC European port, Serbia must have high-capacity rail and road links ready from Trieste into Serbia. This might involve accelerating the upgrade of Corridor X highway/rail (through Slovenia/Croatia to Serbia) , something Serbia can champion in regional forums. Joint lobbying for inclusion of these links in the EU's Trans-European Network plans or World Bank funding would help. Serbia should also consider establishing an “India Hub” logistics park – perhaps a dedicated zone near Belgrade or Niš – that gives Indian firms warehouse and distribution facilities to collect goods from IMEC and dispatch across Europe. On the digital front, both nations could integrate their single-window trade systems and logistics tracking. Electronic data interchange between customs, sharing trade data in advance, and adopting international best practices (like blockchain for supply-chain visibility) would make the flow of goods seamless. Furthermore, cooperation in the digital economy can be institutionalized: for example, Serbia joining India’s Global Digital Public Goods initiatives (such as the UPI payment interface or digital ID) would modernize its services and bind the countries closer. Partnering on telecom and 5G standards, or setting up a joint innovation fund for startups exploring corridor-related tech (logistics tech, agri-tech, etc.), are additional avenues.

Conclusion: Strategic Persuasion

In an era where maps are being redrawn by corridors and connectivity is currency, Serbia and India should move decisively to formalize and elevate their partnership. IMEC has created a narrow but meaningful window for first movers to shape new trade routes and capture early investment gains. If Belgrade and New Delhi hesitate, the map will harden without them, through routes that bypass their interests or partnerships that exclude their influence. But if they act jointly now, they can position themselves at the forefront of Indo-European corridor commerce.

Serbia brings strategic geography, political neutrality, and an open investment climate; India brings scale and technological capacity. The urgency is structural: supply-chain and infrastructure decisions made in 2026 will define industrial placement and gateway winners by 2030. By institutionalizing cooperation, through targeted agreements, dedicated task forces, and high-level dialogue anchored in IMEC integration, both countries can shape the corridor’s logic instead of adapting to it later. The cost of inaction is silent irrelevance; the reward of leadership is durable leverage. Serbia and India should therefore treat IMEC not as a distant blueprint, but as a platform to build a corridor-era partnership with real economic weight and strategic depth.