Feb 19, 2026

Vuk Velebit, Aleksa Jovanović, Petar Ivić

The Middle Corridor and Serbia’s Place in Europe–Asia Trade

Serbia’s strategic role in the Middle Corridor reshaping Europe–Asia trade through connectivity, resilience, and geopolitics

Bridging Asia and Europe – A New Connectivity Opportunity for Belgrade

“Reliable routes connecting Europe and Asia are a geopolitical and economic win for everyone along the way… We need a credible, long-term alternative to the Northern Corridor. Cargo along the Middle Corridor has grown fourfold between 2022 and today,” – European Commissioner Marta Kos.

Geopolitical Shifts and the Rise of the Middle Corridor

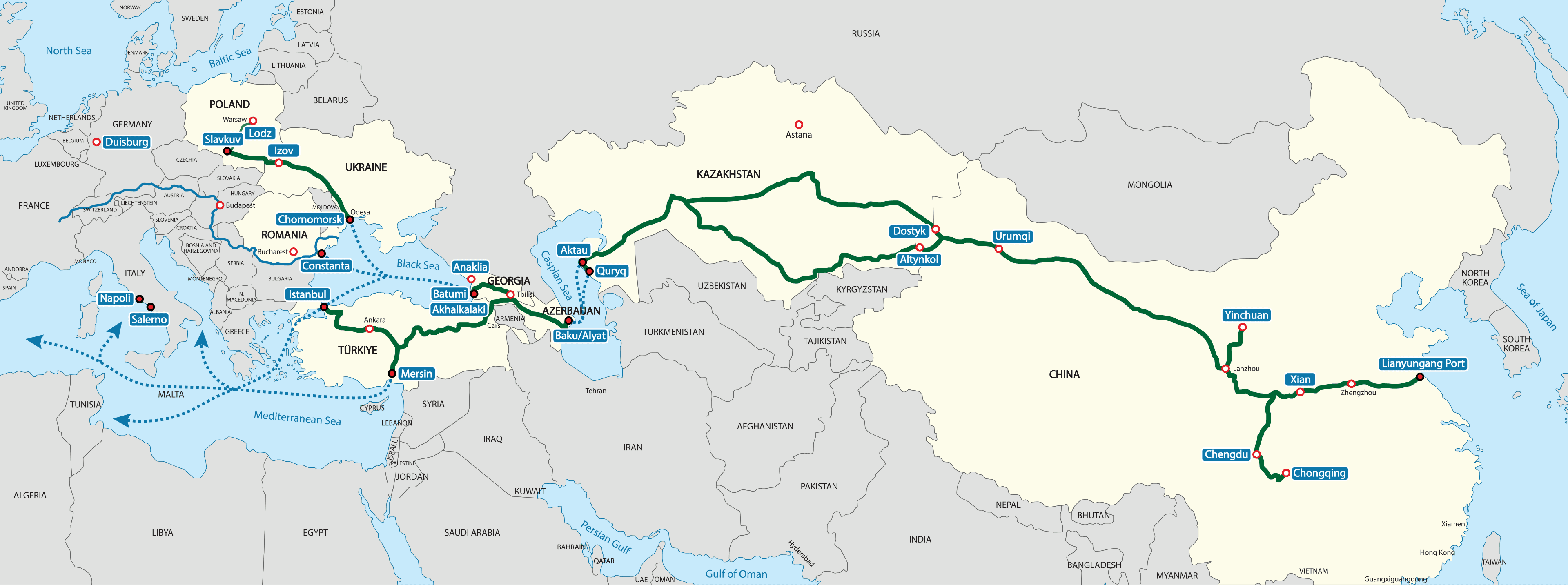

Russia’s war in Ukraine has upended Eurasian trade flows, spurring a search for new transit routes. The traditional overland “Northern Corridor” through Russia and Belarus has become fraught with risk and sanctions, while extended sea routes via the Suez Canal face their own vulnerabilities. Amid these shifts, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, better known as the Middle Corridor, has gained strategic prominence. This multimodal route links China and Central Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea and South Caucasus, entirely bypassing Russian territory. It combines rail, road, and ferry links from Western China across Kazakhstan and the Caspian to Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Türkiye, before reaching European Union markets. By avoiding conflict zones and chokepoints, the Middle Corridor offers a shorter total distance (about 3,000 km less) than the northern route through Russia, making it attractive both geopolitically and commercially.

Map of the Trans-Caspian “Middle Corridor” (green) connecting East Asia to Europe via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and Türkiye.

Over the past two years, the Middle Corridor has transformed from a little-known path into a critical artery of Eurasian connectivity. As Commissioner Kos noted, the volume of cargo moved via this route has surged dramatically, increasing severalfold since 2022. In fact, transit volume nearly doubled to about 1.5–3 million tonnes in 2022, and continues on a sharp upward trajectory. By the first nine months of 2023, the corridor carried 1.9 million tonnes, up 89% year-on-year. This surge reflects a broader realignment of Eurasian supply chains. Shippers are redirecting cargo from sanctioned or insecure routes to this emerging middle path. Central Asian and Caucasus nations have responded by investing in infrastructure, from Kazakhstan’s expanded Aktau/Kuryk ports on the Caspian, to Azerbaijan’s upgraded railways and the new Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway into Turkey. Still, the Middle Corridor’s rapid growth strains its current capacity. Bottlenecks remain, notably the Caspian Sea crossing (limited ferry capacity and weather disruptions) and various rail gauge breaks, border procedures, and tariff misalignments along the way. Without further upgrades and coordination, the corridor cannot yet match the sheer volume of the pre-war Northern route. However, with the right investments to “increase capacity and close gaps,” experts project freight along the Middle Corridor could triple again by 2030. The stage is set for the Middle Corridor to evolve from a contingency route into a permanent pillar of Eurasian trade.

Strategic Appeal As An Alternative Eurasian Gateway

The Middle Corridor’s growing appeal is not just about moving goods faster; it carries strategic weight for the countries involved. Bypassing Russia, it offers a route resilient to geopolitical coercion. “All of us have learnt the hard way that excessive dependencies make us vulnerable. Investments in transport infrastructure… create more options and less risk of blackmail,” Commissioner Kos observed at a high-level forum in Tashkent in late 2025. For the European Union and its partners, the corridor is part of a broader strategy to diversify supply lines under the Global Gateway initiative. At the Trans-Caspian Connectivity Investors Forum in Tashkent, EU officials and Central Asian leaders reaffirmed the “strategic importance of the TCTC as a fast, secure and reliable route connecting Europe and Asia.” They agreed on the need to coordinate action to remove logistical bottlenecks, harmonize regulations, and scale up infrastructure investments along the route. In the words of one analyst, the Middle Corridor has become “a route born of the new Eurasian geopolitics”, offering a viable third corridor that is neither beholden to Moscow nor the congested Suez route.

Another advantage is the corridor’s flexibility and multimodality. It links into various feeder routes, extending east into China’s vast interior and south via connections like the India–Middle East–Europe Corridor (IMEC) announced in 2023. The Middle Corridor’s rail lines and ports can integrate with these new initiatives, potentially forming a web of routes that knit together Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Indeed, plans like IMEC underscore a wider trend: democracies and their partners are building an alternative Eurasian connectivity architecture to ensure that critical trade routes run through friendly, stable territory. Serbia, as a country that straddles key junctures of Europe and Asia, is well-positioned to benefit from and contribute to this emerging infrastructure network.

Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and the Caucasus: A New Silk Road through the Black Sea

The Middle Corridor’s success hinges on the active participation of countries along its path, particularly Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Türkiye. The South Caucasus has re-emerged as a pivotal land bridge between the Caspian region and Europe. Azerbaijan, in particular, is increasingly recognized as a “principal transport and logistics hub” on the corridor. With its ports on the Caspian and control of the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway link, Azerbaijan funnels the flow of goods westward from Central Asia. Equally, Türkiye’s role is indispensable. It provides the overland conduit from the Caucasus into European transport networks. Turkish ports (like Istanbul, Mersin) and railways can channel Middle Corridor freight onward to the Balkans and Central Europe. Notably, Turkey has championed this route through the Organization of Turkic States, and its cargo traffic on the corridor has reportedly increased sixfold over the last decade.

Crucially, these countries see the Middle Corridor not just as a bypass, but as an economic lifeline. By becoming a transit hub, Azerbaijan gains revenue, investment, and strategic clout. “The entire flow of Asian goods through Azerbaijan goes to Europe, where Serbia is located,” observed Serbia’s Trade Minister Jagoda Lazarević, highlighting how Baku’s and Belgrade’s interests intersect on this route. Both Azerbaijan and Serbia have been active participants in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and now both are seizing the opportunity of this “shared transport route” to boost trade ties. Lazarević noted that the partnership between Baku and Belgrade in the Middle Corridor framework is exceptionally dynamic (“world’s second in terms of accelerating performance”) owing to their excellent political relations and complementary economic cooperation. In short, the Middle Corridor opens new opportunities for both Baku and Belgrade, providing “another way to connect our countries, beyond our excellent political and economic relations,” as she stated.

From Serbia’s perspective, deepening links with the Caucasus and Central Asia via this corridor also aligns with its energy diversification strategy. Since 2023, Serbia has been importing Azerbaijani natural gas through a new interconnector, reducing its dependence on Russian supplies. Azerbaijan’s emergence as a reliable energy partner and its integration into corridors like the Southern Gas Corridor have enhanced its importance for Europe. By extending cooperation to transport and logistics (rail, road, ports), Serbia and Azerbaijan are effectively building a comprehensive corridor of connectivity, spanning energy, trade, and infrastructure. As the Pupin Initiative has previously noted, the two countries are transforming their friendship into “a powerful axis of strategic connectivity” in the Balkans-Caucasus region. This axis is mutually beneficial. Azerbaijan expands its reach into European markets through Serbia, and Serbia gains a gateway to the Caspian and Central Asian markets.

Serbia at the Crossroads: A Natural Hub Seeking Integration

For Serbia, the Middle Corridor’s westward extension effectively knocks on its door. Serbia’s geography has always made it a crossroads of East–West and North–South routes in Europe. The Pan-European Transport Corridor X, the north–south highway and rail spine from Salzburg through Belgrade to Thessaloniki, runs straight through the country. Branching off this spine at the city of Niš is the Corridor Xc rail route to Sofia, Bulgaria, continuing onward to Istanbul, Turkey. In essence, Corridor Xc is Serbia’s direct link to the Middle Corridor. Once you reach Istanbul by rail from Serbia, you can connect to the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway heading into the Caucasus, or alternatively ship goods across the Black Sea to Georgia and on to Central Asia. Serbia’s location makes it a natural land bridge between Central Europe and both the Aegean Sea and Turkey, exactly the position one would want to occupy as Middle Corridor traffic increases. Indeed, with borders to seven countries and rail connections to almost all of them, Serbia could establish itself as a regional logistics hub if it fully leverages this strategic location.

However, turning geographic potential into reality requires modern infrastructure, as something Serbia long lacked due to decades of underinvestment in its rail network. Trains in Serbia have historically been slow and unreliable, ceding freight to trucking routes. The good news is that a major modernization is now underway. Backed by the EU and international lenders, Serbia is upgrading its core rail lines to European standards. A landmark project is the reconstruction of the Belgrade–Niš railway (part of Corridor X), a €2.2 billion effort that will cut travel times in half and boost capacity on this key axis. Just as important for East–West trade is the long-neglected Niš–Dimitrovgrad railway (Corridor Xc) connecting to Bulgaria. In March 2024, construction finally began on fully modernizing this 100 km stretch from Niš to the Bulgarian border. The project will upgrade the single-track line, add electrification and modern signaling, and build a new bypass around Niš, eliminating a major bottleneck. Once completed, Serbia will have a fast, electric railway running all the way to Sofia (and onward to Istanbul). This matters enormously for the Middle Corridor: it means freight trains from Central Asia or China can eventually travel via Turkey and Bulgaria straight into Serbia’s network, reaching as far as Budapest or Vienna through onward connections. In technical terms, Corridor Xc will no longer be the “missing link”. It will be a seamless continuation of the Trans-Caspian route into the heart of Southeast Europe. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, EU Ambassador Emanuele Giaufret, and EIB officials all attended the groundbreaking, underscoring the project’s significance for regional connectivity.

Construction work launching the Niš–Dimitrovgrad rail modernization (Corridor Xc) in Pirot, Serbia – March 2024. The EU and European Investment Bank are co-financing this project to better link Serbia with Bulgaria and Türkiye.

The impact of this rail upgrade will be substantial. Currently, the only non-electrified segment of Corridor X in Serbia, the Niš–Dimitrovgrad line, has been a slow, diesel-operated route with limited capacity. Electrifying and refurbishing it will boost train speeds from 50 km/h to 120 km/h, and is projected to increase freight volumes from about 3.2 million to 6.2 million tonnes per year on this line. In addition, annual passenger numbers could triple (from 170,000 to 550,000) once faster, more frequent service is available. In short, Serbia is poised to remove a major choke-point and open a high-capacity corridor toward the Black Sea region. This dovetails with the EU’s broader plan to extend the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) into the Western Balkans. The Niš–Sofia connection is designated as part of the “Orient/East-Med” corridor on the TEN-T map, underscoring its role in linking Europe to Turkey and beyond. EU grants and loans financing this segment show that Brussels views Serbia’s integration into east–west corridors as strategically important. As RailTech noted, the EU and EIB have committed €134 million to transform this once “congested route into a high-capacity corridor” – turning it from a neglected branch into a vital link for Eurasian transit.

Beyond Corridor Xc, Serbia is also looking at complementary east–west linkages. One promising idea is to revive direct rail service between Serbia and Romania, connecting Belgrade to the Black Sea port of Constanța via Timișoara–Belgrade (sometimes dubbed “Rail-2-Sea”). Such a line, if modernized, could plug Serbia into another major corridor (the Three Seas Initiative routes from the Baltic to the Black Sea). It would effectively give Serbian industry an express lane to a Black Sea harbor, further leveraging the Middle Corridor flows that arrive in Constanța by ferry from Georgia. Additionally, Serbia’s position on the Danube River offers a waterway link to the Black Sea. By improving its river ports and intermodal facilities, Serbia can attract more of the westbound Caspian cargo that might be ferried across to Romania or Bulgaria. In other words, Belgrade can become a distribution node where goods coming via the Middle Corridor are forwarded northwest into the EU single market. All these connectivity initiatives, including rail to Bulgaria, rail to Romania, and Danube navigation, strengthen Serbia’s role as the key transit hub of the Balkan peninsula.

Economic and Strategic Stakes for Belgrade and its Partners

Serbia’s embrace of the Middle Corridor carries clear economic incentives. First and foremost is trade diversification. As a landlocked (or rather “river-locked”) country, Serbia depends heavily on a few primary trade routes, chiefly north through Central Europe by truck/train, or south to the port of Thessaloniki by road. The Middle Corridor opens a third axis: eastward to the Caucasus, Central Asia, and China. This can significantly shorten transit times for goods exchanged with Asia. For example, container shipments from China to Europe that take 4–6 weeks by sea could potentially reach Serbia in around 3 weeks via the Middle Corridor, according to industry estimates. Faster transit translates to lower inventory costs and improved supply chain reliability for Serbian importers and exporters. It also makes Serbia more attractive as a location for logistics centers and light manufacturing that rely on timely Asian inputs or serve Asian markets. Indeed, if Belgrade positions itself as a distribution hub at the EU’s external periphery, it could capture added value from sorting, warehousing, and processing goods in transit. We already see interest from Azerbaijani and Turkish logistics firms in setting up operations to handle Middle Corridor cargo in the Balkans.

Moreover, participating in this corridor aligns with Serbia’s strategic goal of being seen as a connector between East and West, rather than a periphery. It enhances Serbia’s leverage in international partnerships. American and European investors take note when a country becomes a transit crossroads. It signals stability, openness, and geostrategic relevance. At the recent Pupin Forum in Washington, experts stressed that “small states like Serbia remain relevant in today’s world – and that strategic connectivity is their best path to success.” In other words, by investing in connectivity (hard infrastructure and soft agreements), Serbia increases its political capital with both Western allies and Asian partners. It demonstrates proactive engagement in solving regional bottlenecks, which earns goodwill. U.S. officials, for instance, have welcomed Serbia’s support for Ukraine and its efforts to integrate with European networks, seeing these as signs that Serbia “stands on the right side of history” and can be a reliable regional partner. Likewise, the EU’s new Growth Plan for the Western Balkans heavily emphasizes connectivity projects, and Serbia’s leadership in this space could accelerate its EU accession trajectory.

There are also strategic security benefits. A more diversified trade network makes Serbia less vulnerable to external pressure. During past crises (like the 1990s embargo or recent pandemic disruptions), Serbia experienced how over-reliance on a single route or supplier can be perilous. The Middle Corridor, by providing an alternate pathway for essential goods (from medical equipment to energy materials), adds resilience to the national economy. It also dovetails with Serbia’s energy diversification. As previously noted, Azerbaijani gas started flowing to Serbia in 2024 via a new pipeline, and discussions are underway to import “green electricity” from Azerbaijan via an undersea Black Sea cable in the coming years. These parallel developments in energy corridors and transport corridors are mutually reinforcing, and both reduce dependence on Russia and create a web of cooperative ties with pro-growth, moderate partners in Asia. This web can act as a buffer against the kind of coercion that Russia exerted over Europe’s gas supply or that any single transit country could exert over critical goods flows. In essence, connectivity is turning into security. Or as the former Serbian PM put it, “in these complex times, not only in Europe but also in the world,” initiatives that bind countries together – like the Pupin Initiative or new corridor projects – are a breath of fresh air that strengthen peace and stability.

But challenges remain, of course. Serbia will need to coordinate closely with neighbors to ensure smooth cross-border operations. Simplifying customs procedures, adopting digital cargo tracking, and aligning rail regulations with EU standards will be essential to truly benefit from the Middle Corridor. There is also competition. Other routes (such as the southerly Trans-Iran corridor or the established Danube river–Constanța route) vie for investment and political support. To secure a lasting role, the Middle Corridor must prove economically viable. This will require continuous reform and investment along the entire chain from Kazakhstan to Europe, something an OECD study stressed when it suggested the corridor should not serve merely as a pass-through for foreign trade, but become an “engine of integration” for the regions it traverses. For Serbia, that means encouraging not just transit but also local industries to plug into this route (for example, by setting up assembly plants that import Asian components via the corridor and export finished goods to the EU). Finally, diplomatic finesse is needed. The Middle Corridor touches many jurisdictions, and Serbia will have to maintain good relations with Turkey, the EU, and the Caucasus states alike to maximize the corridor’s use. Serbia–Azerbaijan Strategic Partnership has set a positive example in this regard, underscoring respect for each other’s territorial integrity and committing to infrastructure cooperation at the highest level. As long as Belgrade continues on this path of multilateral engagement and reforms, the Middle Corridor can be a cornerstone of its foreign economic strategy for the coming decade.

Strategies to Maximize the Middle Corridor’s Benefits

Тhe Middle Corridor presents a timely opportunity for Serbia to enhance its connectivity, resilience, and global standing. To fully capitalize on this Eurasian lifeline, several actions could be implemented:

Complete Key Infrastructure Links and Modernize Logistics: Stay on schedule with the Corridor Xc (Niš–Dimitrovgrad) railway upgrade and related projects, ensuring they meet European standards for speed and capacity. Upon completion, actively market this route to international shippers. Invest in dry ports and logistics hubs near Belgrade and Niš to handle growing freight volumes, and improve intermodal facilities linking rail to road and river.

Deepen Regional Cooperation and Trade Facilitation: Together with Middle Corridor countries (Türkiye, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, etc.), streamline the “soft” infrastructure of cross-border trade. This includes harmonizing customs procedures, adopting digital transit documents, and creating unified tariffs for corridor shipments. Serbia should consider joining relevant coordination platforms of the Trans-Caspian route to voice the interests of Balkan transit states. High-level diplomatic engagement with Ankara, Baku, and Tbilisi, as well as coordination with the EU’s Global Gateway initiatives, will help ensure that the corridor’s Western extension into Southeast Europe is fully operational. In parallel, Serbia can expand free trade agreements and logistics pacts with the Caucasus and Central Asian countries, so that Serbian products can more easily reach those markets via the corridor.

Leverage Western Support and Align with New Corridors: Proactively align Serbia’s development plans with trans-regional corridor initiatives championed by the EU and U.S. The Middle Corridor has strong backing from the EU, and Serbia should continue tapping EU funds (IPA, WBIF) for connectivity, highlighting its role in Europe-Asia supply chains. Simultaneously, Belgrade can explore synergies with emerging projects like the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Serbian diplomacy should seek a seat at the table in planning discussions for these routes, advocating for Balkan linkages. For example, working with Greece and Italy to upgrade rail and port links could channel future IMEC trade through the Balkans. By integrating into multiple corridor networks (north–south and east–west), Serbia will solidify its place as a necessary junction in Eurasian commerce. As one of our previous analyses recommended, “Serbia should join planning talks on IMEC and work with Greece and Italy to upgrade railways and logistics routes” so that goods from Asia can flow through the Balkans to Europe. This strategic foresight will ensure Serbia is not bypassed but rather becomes an indispensable partner in the new era of global connectivity.

Map used for the thumbnail by Tanvir Anjum Adib