Vuk Velebit, Aleksa Jovanović, Petar Ivić

Trieste: Belgrade’s Gateway to Europe’s New Corridors

Trieste as Serbia’s gateway to EU trade, IMEC routes, and strategic Adriatic connectivity

Trieste’s strategic Adriatic port is re-emerging as a vital link between Central and Eastern Europe and global trade routes. For Serbia, a landlocked nation striving for EU integration and diversified partnerships, Trieste offers both a historical connection and a future gateway. This analysis examines why Trieste is so important to Belgrade’s economic and geopolitical ambitions, and how Serbia should engage, through bilateral cooperation with Italy and multilateral initiatives like the Central European Initiative (CEI), to harness Trieste’s full potential.

A Historic Port at the Crossroads of Europe

Trieste sits at the head of the Adriatic Sea, historically serving as Central Europe’s maritime outlet and now positioned to reconnect the Balkans with global trade networks.

Trieste occupies a unique place on the map: at the crossroads of Latin, Germanic, and Slavic Europe. Founded as a free port in 1719 under the Habsburgs, Trieste flourished as the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s primary seaport, overtaking Venice by the 19th century as the dominant northern Adriatic hub. This legacy made Trieste a cosmopolitan entrepôt and a home to Italian, Austrian, Slovenian, Jewish, and indeed Serbian merchants, serving as the empire’s gateway for exports and imports. Even today, the city’s Serbian Orthodox church and multicultural heritage echo those historical ties.

In the 20th century, Trieste’s fortunes waned with shifting borders and the Iron Curtain. After World War I, it was annexed to Italy, cutting off much of its Central European hinterland. During the Cold War, Trieste was geopolitically significant as a meeting point of East and West, but economically sidelined as trade routes bypassed the Adriatic. The port lost ground to rivals like Genoa, especially as Yugoslavia (including Serbia) looked south to ports in the Socialist bloc or its own outlets in the Adriatic. However, the post-Cold War era and EU enlargement brought a resurgence. As Central and Eastern European economies opened and grew, Trieste regained its role as their maritime outlet. The city’s deep-water port (handling over 60 million tons of cargo annually) once again became “indispensable for the landlocked nations of Central and Eastern Europe seeking cost-effective access to global markets.” In short, Trieste has returned to its historic mission as “a true European entrepôt, serving South-Central Europe much as Rotterdam serves North-Central Europe.”

For Serbia, Trieste’s history carries lessons. It was the nearest major seaport for the broader region Serbia inhabits. Serbian traders in past centuries shipped goods through Trieste, forging people-to-people links. Moreover, Trieste’s status as a “historic maritime gateway to Central and Eastern Europe” means its fate has always been intertwined with the Balkans. Understanding this past underscores why Belgrade today views Trieste not as some distant Italian city, but as a natural extension of its own economic geography, an Adriatic lifeline that Serbia once lost and now has an opportunity to regain.

Trieste’s Strategic Value in the 21st Century

Beyond nostalgia, Trieste’s current strategic importance is clear. The port’s geography and capacity make it one of Europe’s most competitive hubs for emerging trade corridors linking Europe with Asia and the Middle East. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has described Trieste as “a crucial hub… the northernmost port of the Mediterranean and a historic maritime gateway to the Balkans and Central and Eastern Europe.” This reflects how Italy sees Trieste: not just a local port, but a strategic asset in a new era of Indo-Mediterranean connectivity.

In 2023, a consortium of countries launched the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a grand initiative to connect South Asia with Europe via the Middle East. While still in planning, IMEC has been hailed as a modern revival of the ancient “Golden Road” trade route. Trieste stands out as the natural European terminus of this corridor. Competing proposals touted Greek ports (like Chinese-operated Piraeus) or Marseille in France, but Trieste offers unparalleled advantages: it is “already better connected than any other port to Central-Eastern Europe” by virtue of its infrastructure. The port boasts direct rail links ferrying goods to Austria, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and beyond. Its road connections through Slovenia into the Balkans further give it logistical reach unmatched by more distant Mediterranean ports.

In short, Trieste is emerging as “the crucial northern segment of IMEC”, leveraging infrastructure already in place to link India and the Middle East to Europe’s industrial heartland. An international forum in Trieste in December 2025 (the Indo-Mediterranean Business Forum) underscored this role, gathering ministers and CEOs from Europe, the Gulf, India, and the Balkans to cement Trieste’s candidacy as IMEC’s European gateway. At that forum, Italy’s leadership emphasized how Trieste could capture the enormous trade flows IMEC promises, aligning it with the EU’s Global Gateway investments and Italy’s own Mattei Plan for the Mediterranean. Notably, delegates from Serbia attended alongside those from other Balkan and Three Seas countries, signaling that the wider region also views IMEC through Trieste as a strategic diversification of trade routes. Indeed, instability in traditional routes (like the Red Sea choke points) has only sharpened interest in an Adriatic gateway for Indo-Pacific commerce. The bottom line is that “Trieste is emerging as one of the most credible European terminals for IMEC,” giving Italy (and by extension its regional partners) a decisive role in shaping new connectivity between India, the Middle East, and Europe.

Integration into European Networks

Trieste’s importance is not limited to far-flung corridors. It is equally crucial within Europe. The port is uniquely integrated into four major Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) corridors, including the Baltic-Adriatic and Mediterranean corridors that link Northern and Southern Europe. As a result, Trieste has become the maritime outlet for a cluster of landlocked EU economies. Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bavaria, and Hungary rely heavily on Trieste for their exports and imports, investing in rail and terminal upgrades to ensure direct access to its docks. Hungary even acquired a stake in a Trieste port terminal in 2019 to secure its trading lifeline. This entrenches Trieste’s role as “a lifeline for landlocked Eastern European nations”, analogous to how Rotterdam serves the inland economies of Western Europe. Notably, Trieste handles over 70% of Turkey’s exports to the EU, illustrating its outsized role in regional commerce.

For Serbia, these facts carry a powerful implication: Trieste is already a conduit for Serbian-relevant trade and can become Serbia’s primary maritime outlet. In many ways, Trieste is “Europe’s bridge to the Western Balkans, as Italy’s Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani phrased it, an entry/exit point where goods bound to or from Serbia can join the main arteries of European and global trade. Unlike smaller Adriatic ports, Trieste has the scale, intermodal facilities, and legal status (as a European free port) to handle high volumes efficiently. IIt'sfree port regime, a legacy from imperial times, streamlines customs and warehousing, benefiting traders from non-EU countries like Serbia. And unlike ports dominated by outside powers, Trieste’s development is aligned with EU standards and openness. All these make Trieste a strategically irreplaceable partner for Serbia’s long-term economic integration with Europe.

The Trieste–Belgrade rail link is a breakthrough, but Belgrade’s real strategic value comes after that point: extending connectivity eastward toward Constanța turns Serbia from a “destination market” into a two-seas corridor hub linking the Adriatic to the Black Sea. Serbia already has rail infrastructure toward Vršac, so the critical missing piece is the Vršac–Timișoara cross-border connection (via Stamora Moravița), which would unlock a continuous logistics chain from Trieste and the TEN-T Adriatic gateways to Romania’s Black Sea port ecosystem. That matters because Constanța sits on the Rhine–Danube TEN-T Core Network Corridor, meaning a functional Trieste–Belgrade–Constanța axis would plug Serbia directly into one of Europe’s main west–east strategic transport backbones, strengthening both trade resilience and geopolitical relevance.

Security and Science Dimensions

Though economics dominate, Trieste’s importance also extends to security and innovation, which are factors not lost on policymakers. NATO planners have noted that secure corridors from the Adriatic to the Baltic are vital for Europe’s defense posture, and Trieste is highlighted as a key node alongside Poland’s and Romania’s ports for military mobility on NATO’s eastern flank. Moreover, Trieste’s hinterland links (including Serbia’s Danube region) give it a role in connecting the Adriatic and Black Sea, which is strategically valuable as the Black Sea faces increasing militarization. In the diplomatic arena, the United States has taken an interest in Trieste’s “pivotal role” in great-power competition, seeing it as a counterweight to rival powers’ influence in Mediterranean trade. And in the realm of innovation, Trieste hosts dozens of scientific institutes and boasts Europe’s highest density of researchers, positioning it as a hub for technology and knowledge exchange. Serbia is pursuing technology partnerships and greater Western investment. Trieste can thus be more than a transit point. It can be a gateway to research networks and high-tech industries in the EU.

Why Trieste Matters for Serbia’s Development

Core interest | Description |

|---|---|

Trade Connectivity and Export Growth | Serbia’s economy, especially its manufacturing and agribusiness sectors, needs efficient access to global markets. As a landlocked country, Serbia currently ships goods via neighboring countries’ ports, notably the port of Bar in Montenegro, Thessaloniki in Greece, and Constanța on the Black Sea for certain exports. Each of these routes has limitations. Bar is small with aging infrastructure. Thessaloniki and Piraeus involve longer sea voyages and reliance on sometimes congested routes, and limited railway infrastructure. By contrast, Trieste provides a direct shot into the heart of the EU. It shortens the supply chain distance to Western and Northern Europe and offers intermodal services straight into EU rail networks. |

Reliable, Diversified Supply Chains | The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions (e.g. war in Ukraine, Suez Canal disruptions) taught Serbia the value of having multiple supply routes. Trieste, as part of an Indo-Mediterranean corridor, diversifies Serbia’s connectivity beyond overland routes through Eurasia or the Turkish Straits. It offers a Mediterranean access point anchored in an EU ally (Italy) known for stable and friendly relations with Serbia. This reduces over-reliance on any single route or country. As an example, the new India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC) via Trieste can complement China’s Belt and Road routes, ensuring Serbia isn’t solely dependent on Chinese-invested infrastructure for Asian trade. |

Energy Security | Trieste’s role in energy logistics is of high importance to Serbia. Serbia has historically imported crude oil via the JANAF/Adria pipeline that connects the Adriatic coast to its Pančevo refinery. Trieste is one terminus of the Trans-Alpine Pipeline network that feeds oil into Central Europe; from there, connections to JANAF mean Trieste effectively helps supply Serbia’s oil needs. As Serbia seeks to reduce dependence on a single supplier (Russia) and build resilience, working with Italy and regional partners on energy corridors is key. The CEI has identified interconnecting gas and electricity grids as priorities, with Trieste seen as a “strategic hub” for new energy routes under initiatives like Three Seas and IMEC. If new pipelines or LNG supply chains emerge via the Adriatic, Serbia would benefit from being tied into Trieste’s hub, gaining access to diversified sources of gas or oil. |

EU Integration and Regional Cooperation: | Every step that improves Serbia’s connectivity with the EU also advances its EU accession prospects. Modern transport links through an EU port like Trieste tighten Serbia’s economic integration with member states. Italy, as a founding EU member, has consistently supported the Western Balkans’ European path, and leveraging Trieste can be part of that story. By championing joint infrastructure with Italy (via Trieste) and within frameworks like the CEI, Serbia shows commitment to regional cooperation, a point that bolsters its image as a constructive player in Europe. Furthermore, engaging through Trieste in multi-country initiatives (from 3SI to pan-European corridors) ensures Serbia is not left out of continental development schemes despite not yet being in the EU. |

Leveraging the CEI and Italy-Serbia Partnership

Belgrade’s engagement with Trieste should happen on multiple levels. A key avenue is the Central European Initiative (CEI), a regional forum that Serbia chaired in 2025, and which uniquely connects Italy with the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe. Notably, the CEI headquarters is in Trieste, a symbolism-rich fact. This city is literally where regional cooperation is anchored. Under Serbia’s CEI Chairmanship, Trieste was naturally featured in the agenda. Serbia prioritized connectivity, organizing meetings in Trieste with the EU-backed Transport Community to plan modernized links across the Western Balkans, Moldova, and Ukraine. During these events, CEI officials hailed the “Port of Trieste as a key asset for regional connectivity,” and Italy’s Foreign Minister Tajani dubbed it “Europe’s bridge to the Western Balkans,” even poetically calling Trieste “the terminal of the Cotton Route” (a nod to the new IMEC trade corridor that complements China’s Silk Road). These endorsements highlight that within the CEI framework, Trieste is viewed as a linchpin for integrating non-EU members like Serbia with the EU’s infrastructure grid.

Serbia should continue leveraging the CEI as a platform to champion projects that link Belgrade and Trieste. The Initiative’s mission since 1989 has been to “bridge the countries of Central and Eastern Europe through dialogue and development”, overcoming divisions. With Italy as a founding member and key supporter, CEI can mobilize funding (often via its connections with the EBRD) for regional infrastructure. Belgrade can propose joint infrastructure grant applications through CEI channels for rail and road improvements along Corridor X (the route from Belgrade to Ljubljana and on to Trieste). The CEI also aligns with the EU’s Three Seas Initiative (3SI) goals in areas like energy and digital links. Here, Serbia’s voice, though not a 3SI member, can be heard via CEI by coordinating with 3SI countries that use Trieste. For instance, Poland or Hungary (3SI leaders) share an interest in Adriatic access; CEI meetings can bring them together with Serbia and Italy to ensure that north-south corridors (like the Baltic-Adriatic rail route) have branches or extensions that include the Western Balkans. In this sense, CEI offers Serbia a backdoor into the club of EU states planning Europe’s future infrastructure – and Trieste is the meeting point of those plans.

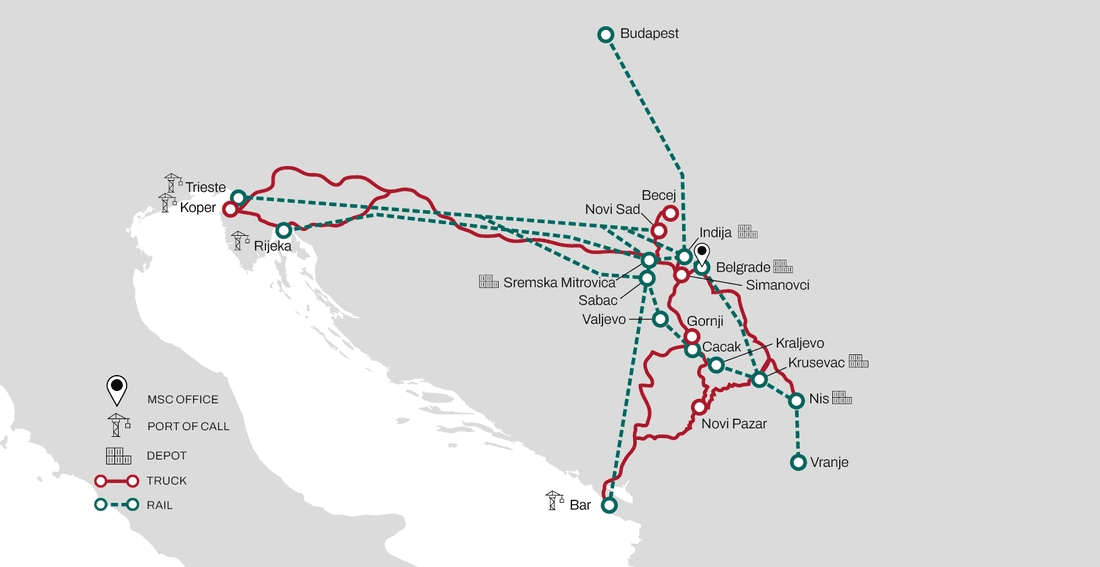

Bilateral cooperation with Italy is the other crucial channel. Italy is one of Serbia’s top economic partners and a strong advocate of its EU bid. With Trieste becoming Italy’s flagship project in the Indo-Med space, Belgrade should tightly align its efforts with Rome’s. A positive example was set in 2023–2024: Serbia and Italy held high-level business forums (one in Belgrade, one in Trieste) that directly led to concrete outcomes in connectivity. By July 2024, an Italy–Serbia intermodal corridor dubbed “Ausava” was launched, linking a logistics hub near Trieste (Cervignano del Friuli) by rail to the new Batajnica intermodal terminal in Belgrade. The project, supported by the Italian Embassy and companies, promised “faster, more efficient, and greener transport of goods” between the two countries. Building on this, global shipping giant MSC in late 2025 started a direct Belgrade–Trieste rail service, enabling Serbian exporters to send freight by train from Belgrade to Trieste’s port and onward to world markets.

Source: msc.com

Belgrade should seek to institutionalize and expand such linkages. For example, it could negotiate a long-term agreement with the Port of Trieste for a dedicated Serbian logistics park or “free zone” area. (Landlocked Austria and Hungary have historically been granted facilities in Trieste; Serbia could achieve something similar to guarantee capacity for its shippers.) Supporting joint ventures between Serbian rail companies and Italian or international logistics firms (like Alpe Adria, which is involved in the Ausava corridor ) can ensure the new train services are sustained and scaled up.

A Roadmap for Belgrade’s Engagement

Given Trieste’s importance, Serbia’s path forward should be proactive and multilayered. Here is a summary roadmap for how Belgrade should engage:

Prioritize Infrastructure Links: Accelerate the upgrade of Corridor X (road and rail) between Belgrade and the Slovenian/Italian border. While highways to Croatia and Slovenia are largely modern, rail lags; the Serbian and Croatian governments, with EU support, should modernize the Belgrade–Zagreb–Ljubljana railway to enable high-speed, high-capacity trains to Trieste. This would complement the new intermodal services and make routing freight via Trieste even more time-competitive. Similarly, exploring a direct Belgrade–Trieste highway route (perhaps through a more direct alignment via Bosnia or via Hungary into Slovenia) could be studied for long-term development. Serbia should also continue improving its domestic logistics nodes, like the Belgrade Batajnica dry port, so they can efficiently handle increasing volumes from Trieste.

Deepen Port Partnerships: Engage with the Port of Trieste authority to secure preferential access or co-investment opportunities. For example, Serbia’s government or private sector could invest in a portion of a new logistics terminal, as Hungary did, to ensure a stake in Trieste’s growth. If full investment is not feasible, long-term contracts for terminal use could be signed, giving Serbian shippers guaranteed slots. Establish a Serbia liaison office in Trieste (perhaps under the auspices of Serbia’s Consulate in Trieste or as a standalone trade office) to coordinate with port officials, CEI Secretariat, and Italian businesses in real time. This on-the-ground presence would demonstrate commitment and facilitate day-to-day cooperation.

Exploit CEI and Regional Frameworks: During and after its CEI Presidency, Serbia must keep the focus on connectivity. It can initiate a CEI working group on Adriatic-Balkan connectivity that meets regularly in Trieste, bringing together transport ministries and railway companies of member states. Concrete projects, such as a Trieste–Belgrade fast freight corridor or harmonizing regulations for intermodal transport, can be pursued under CEI auspices, tapping into CEI’s Cooperation Fund and EU co-financing. Moreover, Serbia should seek observer status or partnerships in the Three Seas Initiative for specific projects. While full membership is for EU states, 3SI’s investment funds or project networks (like Rail-2-Sea linking the Black Sea to Poland) could include branches to Serbia if lobbied correctly. By highlighting how a link to Serbia/Trieste would strengthen 3SI north-south routes, Belgrade can make a win-win case. The fact that Trieste is the Adriatic anchor of 3SI’s North–South corridor is an argument Serbia can use.

Balance East and West by Leveraging Trieste: Serbia has to maintain a balanced foreign policy, but engaging Trieste is a clear path to bolstering ties with the West. As the EU and US endorse IMEC and similar corridors, Serbia’s active role in these shows that it is contributing to global initiatives led by democratic allies. Belgrade should publicize its Trieste-focused projects as part of a strategy of connectivity and openness. The “Cotton Road” via Trieste can complement the “Silk Road”, and Serbia, being central to both,h makes it a more vital partner to all. Diplomatically, Serbia can emphasize its role as a Eurasian transit hub where multiple initiatives meet (China’s, the EU’s, India/Middle East’s). Few countries are better positioned to link the Danube, the Balkans, ns and the Adriatic. Serbia should brand itself as such a logistics linchpin.

Joint Economic Planning with Italy: Serbia and Italy can create a bilateral task force on connectivity and investment. This body could align Serbia’s infrastructure plans (e.g., the national Transport Strategy, railway development plans) with Italy’s port and corridor plans. Italy’s new emphasis on being a “fully maritime nation” with outward projection means there may be Italian funding or expertise available for projects that extend Italian logistics into the Balkans. Serbia could attract Italian investment in sectors like logistics parks, trucking fleets, and manufacturing that relies on Trieste’s supply chain. Regular high-level visits, e.g., making the Trieste Summit an annual Italy-Serbia-Balkans event, would keep momentum. It’s worth noting that Italian diplomacy helped mend ties in the past (Trieste itself was a flashpoint between Italy and Yugoslavia decades ago; now it’s a point of unity). This legacy of cooperation can be highlighted to assure any skeptics that a strong Italy-Serbia partnership benefits the whole region.

Other Analysis

Read time:

15

min

Mar 5, 2026

text

Serbia’s Strategic Depth in Central Asia: A C5+1+ Approach

How Serbia’s partnerships with Central Asia boost energy security, trade, and connectivity

Read time:

5

min

Feb 26, 2026

text

From the Non-Aligned Movement to a Future Alliance Between Belgrade and New Delhi in the New Global Power Game

India’s westward pivot and Serbia’s strategic bet on a deeper economic partnership

Read time:

15

min

Feb 19, 2026

text

The Middle Corridor and Serbia’s Place in Europe–Asia Trade

Serbia’s strategic role in the Middle Corridor reshaping Europe–Asia trade through connectivity, resilience, and geopolitics