Feb 13, 2026

Vuk Velebit

Why China’s Technological Convergence with the West Is Often Overstated

China leads in scale, but true tech power comes from systems, tacit knowledge, and control of critical chokepoints

The prevailing narrative holds that China is rapidly closing the technological gap with the West - and in some domains may already be surpassing it. At first glance, this view appears well supported by headline indicators. China is now the world’s largest R&D spender, produces more STEM graduates than any other country, files more patents than the United States and Europe combined, and accounts for a growing share of global scientific publications. Chinese firms dominate several large industrial technology value chains, including batteries, electric vehicles, solar photovoltaics, and power electronics, and deploy new technologies nationwide at an exceptional speed. In selected frontier-adjacent domains, particularly artificial intelligence, Chinese institutions rank near the top globally in publications, benchmarks, and applications. These outcomes are commonly attributed to China’s model of state coordination and industrial policy, which emphasizes centralized planning, long time horizons, and large-scale mobilization of capital, infrastructure, and talent - often contrasted with regulatory fragmentation and political constraints in advanced Western economies.

This interpretation, however, relies on a narrow conception of technological power. Many commonly cited indicators capture scale, diffusion, and engineering optimization, but they do not adequately measure control over frontier technologies, technological choke points, intellectual property, standards-setting, or the accumulation of tacit knowledge that underpins long-run innovation leadership and the creation of entirely new industries.

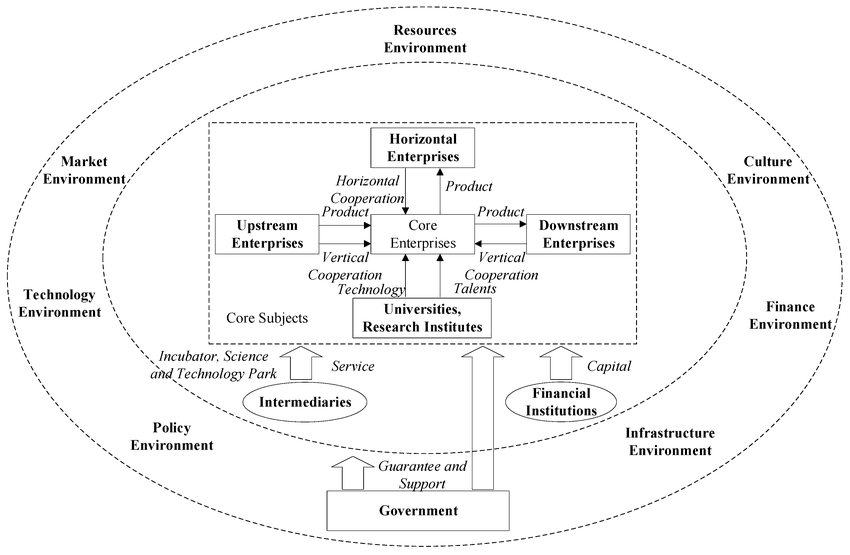

Innovation outcomes are shaped less by inputs than by institutional systems that govern how resources are selected and transformed into capability. China’s innovation model is tightly coupled to industrial policy, state priorities, and state-aligned national champions. This architecture has proven highly effective at scaling established technological trajectories - coordinating supply chains, compressing manufacturing learning curves, and driving down costs through process innovation and system integration. At the same time, it systematically favors incumbent-led, plan-legible innovation. Deviating from prioritized pathways can carry political and financial penalties, biasing selection toward incremental improvement and filtering out radical uncertainty.

This bias matters because frontier innovation depends disproportionately on experimentation, failure tolerance, and tacit knowledge accumulation. Many breakthrough technologies emerge not from scale alone, but from decentralized discovery processes in which uncertainty is embraced, and learning is iterative. Tacit knowledge - deep know-how embedded in people, organizations, and production routines - is difficult to codify or replicate through formal planning, yet it is central to sustained technological leadership.

Advanced semiconductors illustrate how these institutional differences translate into technological limits. China has rapidly expanded capacity and achieved global competitiveness at mature technology nodes, where scaling, yield optimization, and coordination dominate. At the frontier, however, progress remains constrained by dependence on critical equipment, design tools, and process knowledge that emerged through decades of decentralized experimentation across U.S., European, and Japanese ecosystems. The binding constraint is not capital or engineering talent, but deeply embedded cumulative know-how and tightly coupled supplier–tool–process ecosystems.

Western innovation systems are structured to generate such frontier breakthroughs through entry and competition. They are oriented toward “zero-to-one” innovation via competitive entry, venture capital, and decentralized discovery. Startups are not inherently superior, but they face incentives to pursue disruptive trajectories that incumbents often avoid, including technologies that cannibalize existing markets or lack immediate commercial clarity. A large body of empirical research suggests that entry-driven systems are more likely to generate new technological categories and core intellectual property, even if latecomers later excel at scaling and industrial deployment.

A second, less visible constraint on China’s convergence is strategic selectivity across technological domains. Chinese policymakers have deliberately de-prioritized several legacy but still foundational areas where Western incumbents possess entrenched advantages built over decades. These include advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, electronic design automation (EDA) software, aerospace propulsion and safety-critical aviation systems, high-end scientific instrumentation and metrology, and pharmaceutical originator R&D governed by Western regulatory science.

China’s focus on emerging sectors where incumbency is weaker encounters a structural ceiling. Even future-facing technologies remain dependent on foundational infrastructures that continue to be controlled by the United States and its allies. Semiconductors again provide the clearest illustration: despite massive investment and impressive optimization under constraint, Chinese firms remain unable to manufacture at the leading edge at commercial scale. Dependence on technological choke points - most notably advanced lithography systems, process-control tools, and the surrounding ecosystems of tacit knowledge, supplier relationships, and intellectual property - cannot be rapidly overcome.

Comparable dependencies persist across other strategic sectors. China deploys artificial intelligence at scale, yet frontier model training depends on advanced compute architectures, software frameworks, and semiconductor supply chains anchored in the U.S.-led ecosystem. China dominates electric vehicle manufacturing, but critical power semiconductors, design tools, and production equipment remain Western-controlled. China manufactures pharmaceuticals efficiently, but global acceptance of novel drugs continues to be governed by Western regulatory institutions and standards.

Aggregate R&D metrics further obscure a fundamental difference in system architecture. The Western innovation system does not operate as a collection of national silos, but as a deeply integrated transnational network spanning the United States, core EU economies, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, Israel, Switzerland, Canada, and Australia. This network is unified by interoperable IP regimes, standards-setting bodies, certification systems, capital markets, and high levels of talent mobility.

Such networked systems generate multiplicative and durable advantages. They enable fine-grained specialization, disperse technological risk, and allow rapid recombination of breakthroughs across domains. High-value Western innovation is disproportionately internationalized, while China’s innovation output - despite its scale - remains more nationally concentrated and hierarchically organized.

The implication is not that China lacks technological capability or momentum, but that convergence is frequently overstated. Headline indicators tend to equate scale and deployment with control over technological primitives and innovation ecosystems. In practice, the competition is not China versus individual Western countries, but a hierarchical, state-centered system versus a networked technological civilization anchored in shared institutions, trusted IP frameworks, and accumulated tacit knowledge. These architectures convert resources into technological power in fundamentally different ways - and that distinction remains central to assessing the durability of Western technological leadership.